This article is part of the Hidden Canada series – a collaboration between ACO NextGen and students from the University of Toronto. In their seminar on Canadian architecture and landscapes, students were asked to focus on little-studied aspects of the built environment in Canada, or to approach well-known places from a fresh perspective. These articles are the result of their exploration.

In the fall of 1964, the first appointed pastor of St. Mary’s Parish, Father Werner Merx, approached Douglas Cardinal to help conceptualize the design for a community church. At this point, Cardinal was in the primary stages of a soon-to-be internationally renowned career as an architect. Even in these early years, Cardinal’s talent was apparent. He welcomed the challenge provided by Father Merx, who believed that the building must encompass the future of Catholic worship – a future that welcomed community and peace, while facilitating a sense of spiritualism that could be understood by everyone.

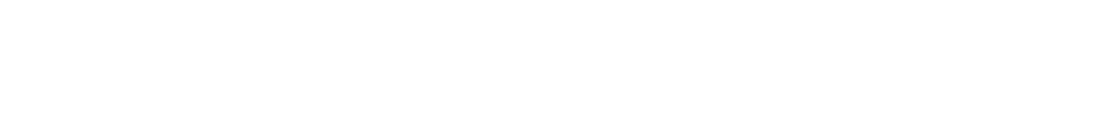

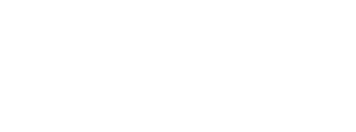

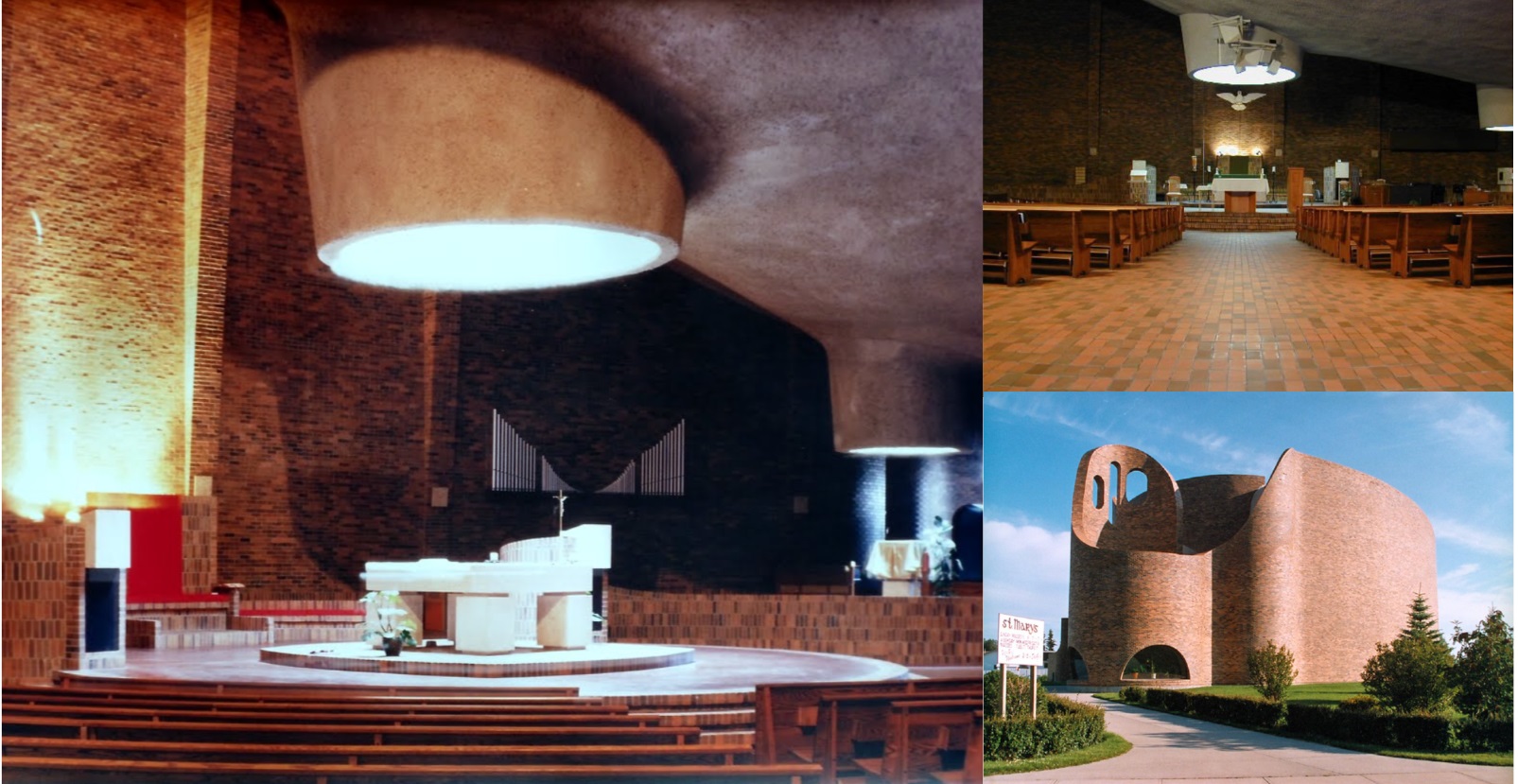

Today, St. Mary’s Church stands as a sublime mass of brick and concrete in the community of Red Deer, Alberta. The façade consists of continuous brick walls which unfold like massive scrolls and replicate the rise and fall of Alberta’s topography. Inside a remarkably spacious worship room sits two altars, each bathed in streams of sunlight allowed by circular apertures cut from the sloped roof. These naturally derived spotlights marry the interior with spiritualism.

“Everything had to be a spiritual act” said Cardinal in a 2021 interview with the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture. “All our buildings should be spiritual places.”

Both Douglas Cardinal and Father Merx rejected the basilica plan and elevation which have now become the visual paradigms of Catholic churches, opting instead for a space that would be less hierarchical. According to Cardinal’s website, the circular design of St. Mary’s Church allows for the community to come together and share the building’s harmonic effects. The worship room especially facilitates a shared environment, with its spherical interior (a principle of Indigenous architecture) both symbolizing and encouraging a personal connection between its inhabitants.

Cardinal was born of Blackfoot and Métis descent and has had an admiration for architecture since high school. Yet, a childhood in Catholic residential schooling resulted in a traumatic past not unfamiliar to members of First Nations communities. These experiences also alerted Cardinal to a major shortcoming in North American architecture, which derived from the influence of colonizers early in Canada’s history. So many buildings had become nothing more than empty shells or mere reflections of the hastily erected housing complexes made to accommodate an influx of settlers into Canada.

“I was concerned about the environment and how buildings didn’t truly fulfill the needs of people,” said Cardinal in a 2018 speech at the University of Calgary, during which he encouraged Indigenous students to continue on their paths to becoming architects. It became an ambition of Cardinal’s to reinstall purpose to architecture that transcended functional practicality. He did so by using the various methodologies of Indigenous architecture and design. In his book about the architect, John Reid Acland describes the ways in which Cardinal applies Indigenous principles to the composition of St. Mary’s Church. Namely, he claims the concept of movement is a powerful tenet, with the moving line capable of communicating certain ideas to the viewer. Movement is carried out in the scrolling, fluctuating walls of St. Mary’s Church (the highest point of which reaches 47 feet high). They reflect the dynamic harmony and spiritualism that Cardinal and Father Merx conceptualized during their meetings prior to construction.

Another aspect of traditional Indigenous architecture is an acute attention to landscape and nature, something Cardinal directly applied to the most challenging aspect of the church’s audacious design. As he recounted during the interview with the John H. Daniels faculty, the logistics of a dramatically sloped roof (which was imperative to the interior of the worship room) were difficult to execute. To solve the problem, he turned to his surroundings:

“I watched a spider build a web, and I thought my goodness that’s my solution for the roof!”

Echoing the equilibrium of a spider’s web, Cardinal decided to have the roof supported by a skeleton of lightweight Styrofoam beams surrounded by concrete. This technique allowed the Church’s roof to slope almost impossibly inward, creating an effect that likely evokes the rethinking of material reality altogether. Upon entering the main worship room of Saint Mary’s Church, the viewer is confronted with a spiritually charged atmosphere. It is a sombre space of meditation inspired by the problem-solving resilience of nature.

The monumental design of St. Mary’s Church can be attributed to Cardinal’s application of Indigenous architectural traditions – namely an awareness of landscape and movement – to breathe life back into the buildings with which we react. It can be argued that nowhere is this more important than in a space dedicated to the appreciation of spirit.

This article was originally published by ACO NextGen on May 25, 2021; reprinted with permission.