This article is part of the Hidden Canada series – a collaboration between ACO NextGen and students from the University of Toronto. In their seminar on Canadian architecture and landscapes, students were asked to focus on little-studied aspects of the built environment in Canada, or to approach well-known places from a fresh perspective. These articles are the result of their exploration.

The Anishinaabek Discovery Centre (ADC) is the new home of Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig (SKG), an Indigenous post-secondary institute that runs in conjunction with Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. Completed in 2019, the Centre houses classrooms and administrative offices, a student lounge, café, art gallery as well as a performing arts space. In addition to the state-of-the-art libraries and archives, the National Chief’s Library is the first-ever First Nations-organized and First Nations-run research library in Canada. The ADC was funded by the federal government’s Strategic Innovation Fund and its design takes into consideration the Anishinaabe teachings with a land and culture-based curriculum.

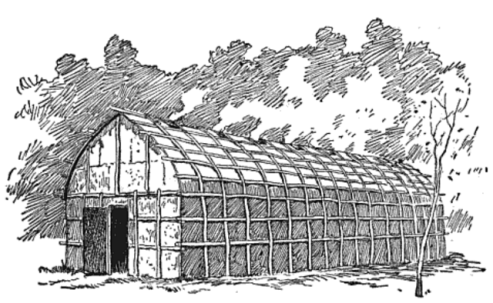

The ADC was designed by First Nations-based and Indigenous-owned firm Two Row Architect. Set out to promote architecture that has a positive impact on the land and environment, Two Row are concerned with how the building and its design can serve the Indigenous community. With this philosophy in mind, the ADC takes inspiration from Ojibwe Chief Shingwaukonse (1773-1854) and his vision for the “Teaching Wigwam”, a cross-cultural educational project intended to assure proper education for Anishinaabe students. Through the SKG initiative, this vision is finally realized almost two centuries after its initiation.

Two Row Architect design buildings and public spaces that create a sense of community while honouring the land. They establish a connection to the land by integrating the surrounding environment into their design. The Seneca College Newnham campus in Toronto Ontario is another one of their projects that incorporates aspects of traditional Indigenous knowledge into a modern design. The structure alludes to the Haudenasaunee longhouse and its design features work together as an extension into the surrounding landscape. These elements constitute a space that is immediately recognizable as Indigenous and serves to further promote and educate the public on Indigenous culture and design.

The design of the ADC incorporates traditional Indigenous styles in modern ways with unique features such as the 24-foot-tall barrel-vault timber roof crafted of spruce. The dome structure mimics that of a traditional Anishinaabe longhouse. Special construction processes had to be implemented to ensure the building would be fire and water-resistant. This was done using the Japanese charring process Shou Sugi Ban, preserving the wood by charring it. To ensure an open and flexible design, custom insulated concrete form (ICF) had to be used to shape the curve of the building.

With many unique features of the centre that stand out, perhaps the most significant are the archives that provide a safe space to share and appreciate Indigenous artifacts. The archives are open to the local Indigenous community, allowing for a more immersive and secure transmission of knowledge. Along with a gallery and library, the archives provide an accessible space for Indigenous-created information and Indigenous-related research for students.

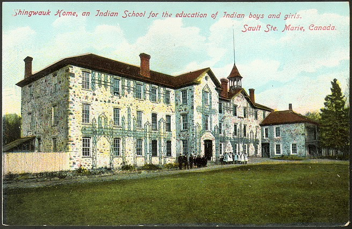

The land on which the university now stands was once part of the Canadian residential school system. Algoma University’s main Shingwauk Hall building housed the Shingwauk Residential School that operated from 1873 until its closing in 1970. In effort to further commit to reconciliation, the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre (SRSC) published Healing and Reconciliation Through Education in 2019, an e-book providing an extensive history of the residential school, including decades of archival research and data collection. Working closely with the residential school survivors, descendants, friends, students, and staff who form the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association (CSAA), the SRSC work to restore and realize Chief Shingwaukonse’s vision of providing an environment for Indigenous people that promotes “sharing, healing and learning”.

Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig is one of eight Indigenous-owned and operating institutes that comprise the Indigenous Institutes Consortium (IIC) in Ontario. In a report published by the IIC in 2019, it was concluded that the SKG upholds Chief Shingwaukonse’s original vision of a “teaching wigwam where his people could acquire the necessary educational tools in modern society without comprising the values of our culture and traditions”. With this goal in mind, SKG expands and modernizes their institute with the new Discovery Centre without having to comprise these values.

The implementation of a new centre designed for and by Indigenous peoples, reinforces Chief Shingwaukonse’s pursuit of providing an accessible, Indigenous-based education in a shared environment that promotes unity and healing. The ADC displays a modern take on traditional Indigenous design, reflecting the importance of culture-based learning that extends well beyond the conventional academic settings. By promoting and preserving Indigenous culture and education, the centre is a testament to the commitment to reconciliation, further showcasing the importance of community achievement. With a design that emphasizes the importance of reflecting Indigenous beliefs, the Anishinaabek Discovery Centre is instrumental in expressing and contextualising traditional knowledge, to educate and promote Indigenous culture for generations to come.

This article was originally published by ACO NextGen on June 15, 2021; reprinted with permission.