This article is part of the Hidden Canada series – a collaboration between ACO NextGen and students from the University of Toronto. In their seminar on Canadian architecture and landscapes, students were asked to focus on little-studied aspects of the built environment in Canada, or to approach well-known places from a fresh perspective. These articles are the result of their exploration.

Wong Dai Sin Temple, an asymmetrical concrete building with an elevated main body, is an unusual presence in the community of Markham and serves as a spiritual space for The Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism.

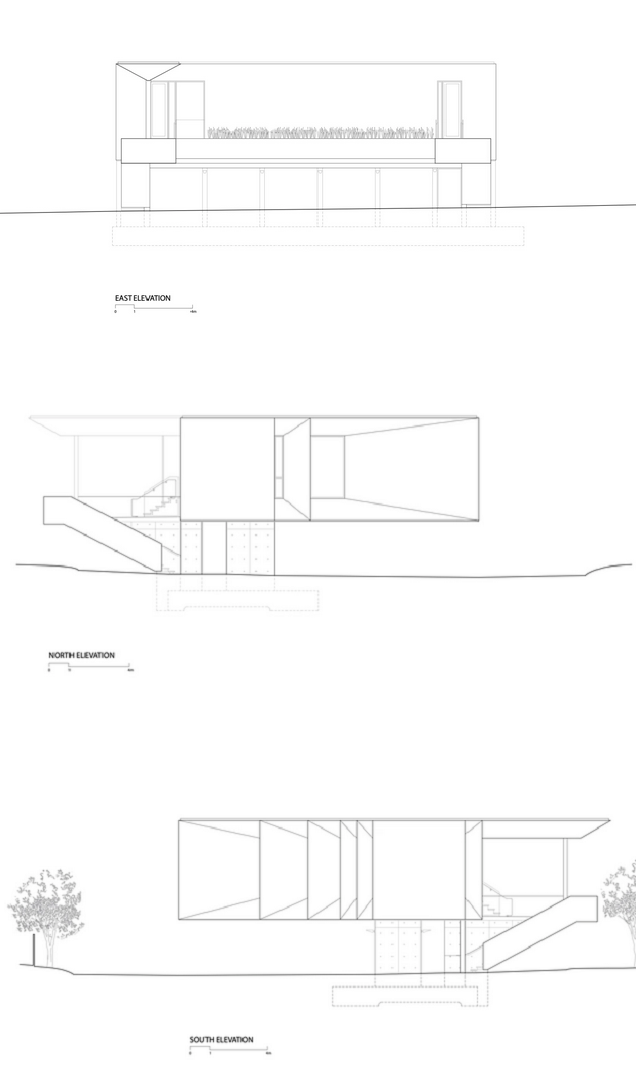

The temple was designed by Brigitte Shim and her partner A. Howard Sutcliffe in 2015. Built in a contemporary style, the main worship space, a rectangular concrete slab, is supported by a 10.2m cantilever. The elevated slab and the parking ground underneath are reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye in the 1930s. Thanks to developing technology, elevations of both the east and west sides of the temple are made possible by the cantilever and seven concrete piers.

As the spiritual centre of the Taoist community, its location is not what we might expect for a temple. As Archdaily reports, “this place of worship is located on a major suburban arterial road surrounded by a shopping mall and cul de sac[s] lined with oversized single family residential mansions.” It is located in a modern suburb, and the need for ample parking space directly led to its elevation off the ground. Markham is full of parking lots and yet, the city requires places of worship to have a minimum number of spots for cars. So, it seems the city plan forced the design. However, the spiritual look and elevated areas also provides space for people to practice Tai chi. Eventually, the architects found a way to balance the opposition between the spiritual integrity and strict parking requirements.

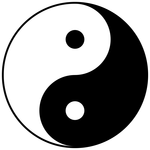

The soul of Taoism is perfectly embedded in both the design and the surrounding environment. The alternative name for Taoism is Daoism. “Daoism” originated from the Chinese word “Dao,” which means “road” or “the way” in English. The most well-known symbol of Taoism in the west may be the Yin-Yang symbol in black and white. This symbol represents the concept of dualism in Taoism. The opposite sides co-exists with no conflict, and instead their interconnection complements one another.

The soul of Taoism is perfectly embedded in both the design and the surrounding environment. The alternative name for Taoism is Daoism. “Daoism” originated from the Chinese word “Dao,” which means “road” or “the way” in English. The most well-known symbol of Taoism in the west may be the Yin-Yang symbol in black and white. This symbol represents the concept of dualism in Taoism. The opposite sides co-exists with no conflict, and instead their interconnection complements one another.

Shim-Sutcliffe endeavour to bring the interconnection of construction and community into their architectural designs. Their Laneway House is another example that best illustrates the Taoist spirit of Yin-Yang.

As the embodiment of a small community in the green space of a city, the Laneway House also exemplifies the Taoist co-existence with the external environment. As Brigitte Shim states in Better Dwelling, the presence of houses in small laneways creates the potential of intimate community clusters. On a smaller scale, such a community can exist with flexibility within the bigger city. To draw a parallel between the Laneway House and the temple, the Taoist community in Markham fits the Asian Taoist culture into a modern, urban background. Like the Yin-Yang symbol, the Taoism community and urban Markham have turned the two opposites into one integrated unit.

Some Taoist community members focus on the principle of “stillness within the movement” and look for harmony within conflict. This principle might well have applied to the original design. In fact, behind the construction, there were more conflicts than people may imagine. The Toronto Star reported that the neighbourhood was quite unwilling to approve of a project that would require even more parking lots in a city already overwhelmed by them. Some local politicians fought against the temple as well. The problem ended with a compromise – the elevated design creates parking space without increasing the building’s footprint. This compromise eventually led to the current living system between the building and the community.

Indeed, the complementary interconnection between opposing sides is the leading spirit of Taoism. This spirit extends to the relationship between Shim-Sutcliffe’s building and the external environment. For the Wong Dai Sin Temple the seemingly unresolvable conflict between the temple and whoever stands against it eventually found a suitable balance. The relationship between the parking requirements and the design evolved from a conflict to a harmonious co-existence. The temple works as a religious sphere that has adapted to the modern requirements of a city.

This article was originally published by ACO NextGen on June 8, 2021; reprinted with permission.