Re:THINK is an online collection of teaching articles, edited and produced by the Centre for Teaching Support & Innovation at the University of Toronto.

When the University of Toronto moved to an entirely online/remote teaching environment in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic, instructors, staff, and students pivoted quickly and, for some, there was a steep learning curve. Re:THINK developed a series focusing on instructor experiences – how they connected with students and colleagues, the creative ways they approached the transition, and the challenges they faced and resources they discovered while doing so. Samantha Chang (PhD Candidiate, Department of Art History) was asked to contribute to this series and her article, "Being Present in the Online Learning Environment," discusses her course development and the challenge of how to encourage active engagement with learners and with art during the lockdown.

Samantha's original article can be accessed on the Re:THINK website.

Being Present in the Online Learning Environment

By ReTHINK - 03/06/2020

Samantha Chang

Humanities Trainer, Teaching Assistants’ Training Program

PhD Candidate, Department of Art History

How many of us have rediscovered our personal living space in the last two months? In March 2020, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles issued a playful challenge via social media, asking people to re-create their favourite artwork using just three objects from their home. Since then, thousands of entries have flooded Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook.

It was also in March 2020 when I received my offer letter to teach the first-year undergraduate art history survey course in the May–June summer session. The offer included the following caveat: “Please note that, in keeping with current circumstances, this course may be delivered online instead of in-person as determined by the Faculty or Department.” In the previous iteration of the course, I accompanied students on museum and gallery visits to engage with art objects directly. How do I encourage active engagement with my learners and with art during the lockdown?

Rethinking the Online Course Syllabus

My first step in encouraging active engagement in the online classroom is rethinking the course syllabus design. The main goal of the syllabus is to facilitate learners “to take responsibility for their learning” (Grunert O’Brien, Millis, & Cohen, 2008, p. 5). Instead of a static document, the online course syllabi provide flexibility for incorporating multimedia and interactive elements such as videos and quizzes. An introduction/orientation video reassures learners that there is a smiling and enthusiastic human being behind the course design. The video (Figure 1) allows me to act as a guide in preparation for the learner’s tour of Quercus and reassures learners that “I am here; I am present” during their learning process (Boettcher & Conrad, 2016).

Video 1. Introduction/orientation video for The Faces of Art History.

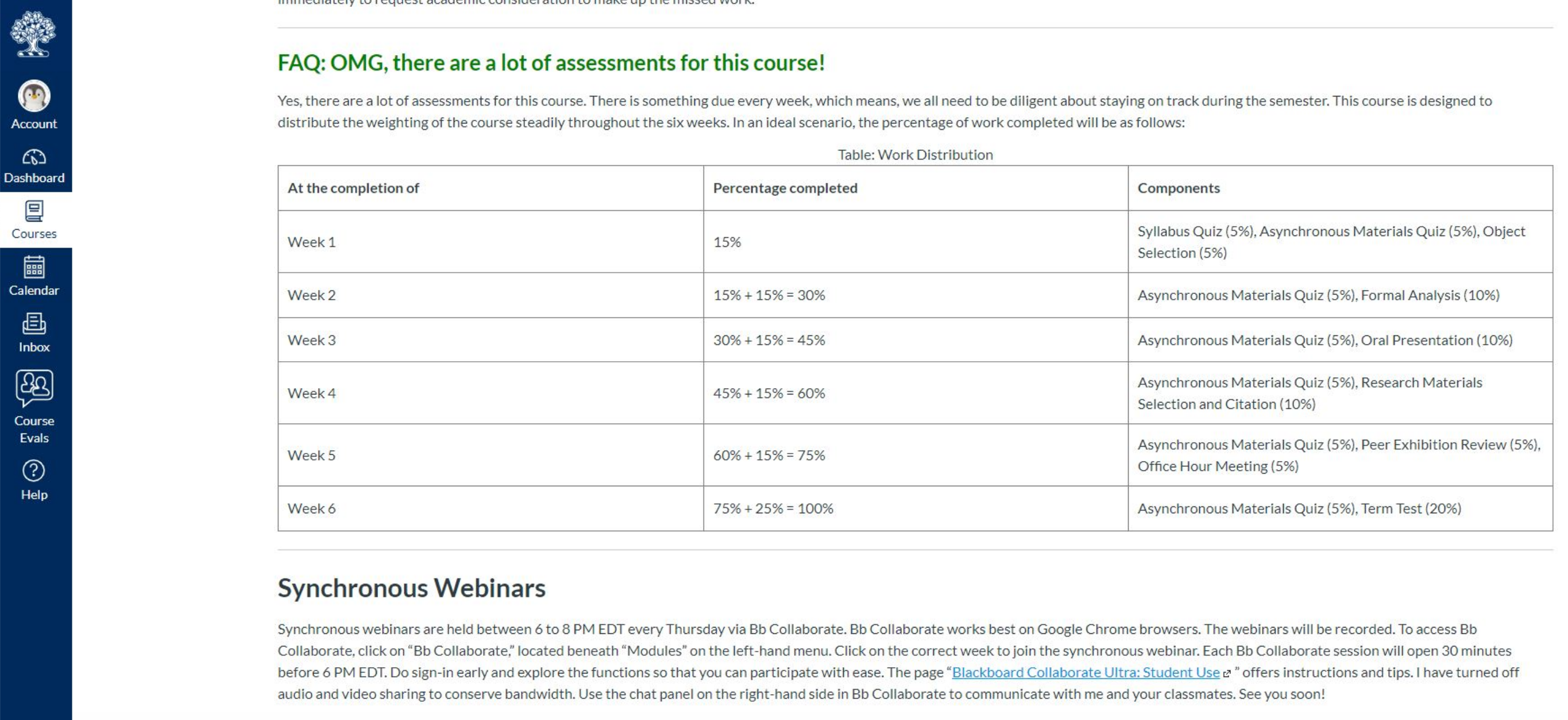

Unlike an in-person syllabus walkthrough, the online course syllabus provides learners with the opportunity to “discover” how the course will unfold during the semester (Weimer, 2002, pp. 83–84; Fornaciari & Lund Dean, 2014, p. 712). The syllabus can anticipate learners’ questions and address concerns via FAQ boxes (Figure 2) inserted throughout the syllabus.

Figure 2. Quercus screenshot displaying inserted FAQ boxes.

But what about all the questions and concerns that I did not anticipate as a Course Instructor? How do I give voice to our learners from day one in an online environment? In this iteration of the first-year undergraduate art history survey course, I included a syllabus quiz. The quiz serves two objectives: first, to encourage learners to read and use the syllabus as a resource throughout the semester; second, to present a space for learners to share their interests, expectations, and worries about this course. The quiz also offers an opportunity to demonstrate how we can easily engage in active art history, even within our personal living space. An abbreviated version of the quiz is provided below. The type of Quercus quiz question is indicated in brackets. (Note: The “Essay” quiz question option provides a text box. Learners do not need to compose an essay.)

- Have you taken any undergraduate art history courses in the past? Why are you taking this course this summer? What are you hoping to achieve and learn in this course? Do you have any concerns or expectations that you would like to share with me? Type your response in the text box below. Short answers are sufficient. [Essay Question]

- What is your favourite work of art, artist, or museum/gallery? Why is it your favourite? Type your response in the text box below. Short answers are sufficient. [Essay Question]

- Although we cannot physically visit museums and galleries during the lockdown, many art institutions have asked art lovers to re-create iconic artworks at home. These memes are found in abundance on Instagram and Twitter. As part of this syllabus quiz, find, download, and upload your favourite art meme below. Accepted file formats: GIF, JPG, JPEG, PNG, TIFF. The meme can be from the #gettymuseumchallenge or any art meme that you have stumbled upon. I look forward to seeing what you find! [File Upload]

- Match the assessments to their correct due date from the dropdown menus below. [Matching]

- Please read the “Academic Integrity Checklist” and type out your full name and date in the text box below to acknowledge that these statements will hold true for all assignments submitted for this course—for example, Samantha Chang, May 1, 2020. The following statement is adapted from the Teaching Assistants’ Training Program. [Essay]

Each of the five syllabus quiz questions reinforces the importance of “presence” in an online learning environment. Question one delves into the learner’s mind, what Boettcher & Conrad would call “a getting-acquainted cognitive post” (2016, p. 138), while question two builds connections, a “getting-acquainted social post” (2016, p. 136). Question three, the art meme prompt (Figure 3), reinforces the social connection and prompts learners to begin their art history discovery by starting with representations that may be familiar and are relevant to them.

Figure 3. Collage of art meme submissions. [GIF]

From Technology to Community

Establishing the presence and initial connection with students is one thing; however, how do I maintain active engagement from week-to-week? In this first-year undergraduate art history survey course, synchronous webinar sessions are held weekly via Bb Collaborate. At the start of each live session, I turn on my webcam and use the ten minutes at the top of the hour to check-in with my students: How has your week been? Did you watch or read anything interesting this week? Was there anything in the asynchronous material that was surprising? To launch the conversation, I reflect on my week both on camera and in the Bb Collaborate chat panel. I describe a few of the art memes submitted by learners that relate to my week. At this point, several learners will type in the chat panel excitedly about how they were the ones who submitted the meme and comment on how their week has been. Usually, when one person shares their experience, such as trying unsuccessfully to find a book online, another will chime in, and a cascade of shared experiences appears. The ten-minute conversation at the start of each live webinars transforms the technology platform to an online community.

But why memes? How are memes relevant to art history? Art history gives us unique access to the past because of the way objects document and express ideas, emotions, and viewpoints. My decision to incorporate memes this semester stems from the fact that art re-creations and memes have become increasingly popular since the lockdown. This popular format provides a gateway to examining theories of representation and visual perception. Although I can no longer accompany students on museum and gallery visits, I can generate various modes of exploration with the course material. The art re-creations and memes remind us that while online learning is challenging, we can try to find the humour and the upside to every situation by being present and together for one another.

Works Cited

Boettcher, J. V., & Conrad, R.-M. (2016). The online teaching survival guide: Simple and practical pedagogical tips (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Fornaciari, C. J., & Lund Dean, K. (2014). The 21st-century syllabus: From pedagogy to andragogy. Journal of Management Education, 38(5), 701–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562913504763

Grunert O’Brien, J., Millis, B. J., & Cohen, M. W. (2008). The course syllabus: A learning-centered approach (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice. John Wiley & Sons.

This article was originally published by Re:THINK on 03/06/2020; reprinted with permission.