A group of University of Toronto students from two very different disciplines have teamed up to uncover secrets behind a museum collection that spans prehistory to the mid-20th century.

The academic detective work was done on selected pieces from The Malcove Collection, a permanent display of art located at U of T’s Art Museum. The goal was to help fill some of the blanks in the collection by a true merger of the arts and sciences.

The collection itself was donated by Lillian Malcove, a Freudian psychoanalyst who had gathered more than 500 objects over a 50-year period. However, little was known about the history behind many of the museum’s artifacts. A detailed material analysis was needed to help trace its history – a challenge that was tackled through two Jackman Scholars-in-Residence (SiR) projects. The SiR program is an intensive four-week interdisciplinary residency in social science research for upper-year graduates.

“When basic information is missing, it means researchers and teachers don’t use it because they want to be able to tell their class about its history,” says Erin Webster, an associate professor, teaching stream, in U of T Scarborough’s department of arts, culture and media. “Having that concrete, factual identification is going to make it easier to use the collection in the future.”

While Webster’s group had knowledge of art history, a group of students led by Alen Hadzovic, an associate professor, teaching stream, in U of T Scarborough’s department of physical and environmental sciences, was able to lend their expertise in technology and chemistry to identify materials used in a few of the collection’s pieces.

Webster had used pieces from the collection in her classes before, but the more she worked with the collection the more she realized the need for collaboration.

“We really wanted to showcase the knowledge that could be developed by students working across disciplines,” Webster says.

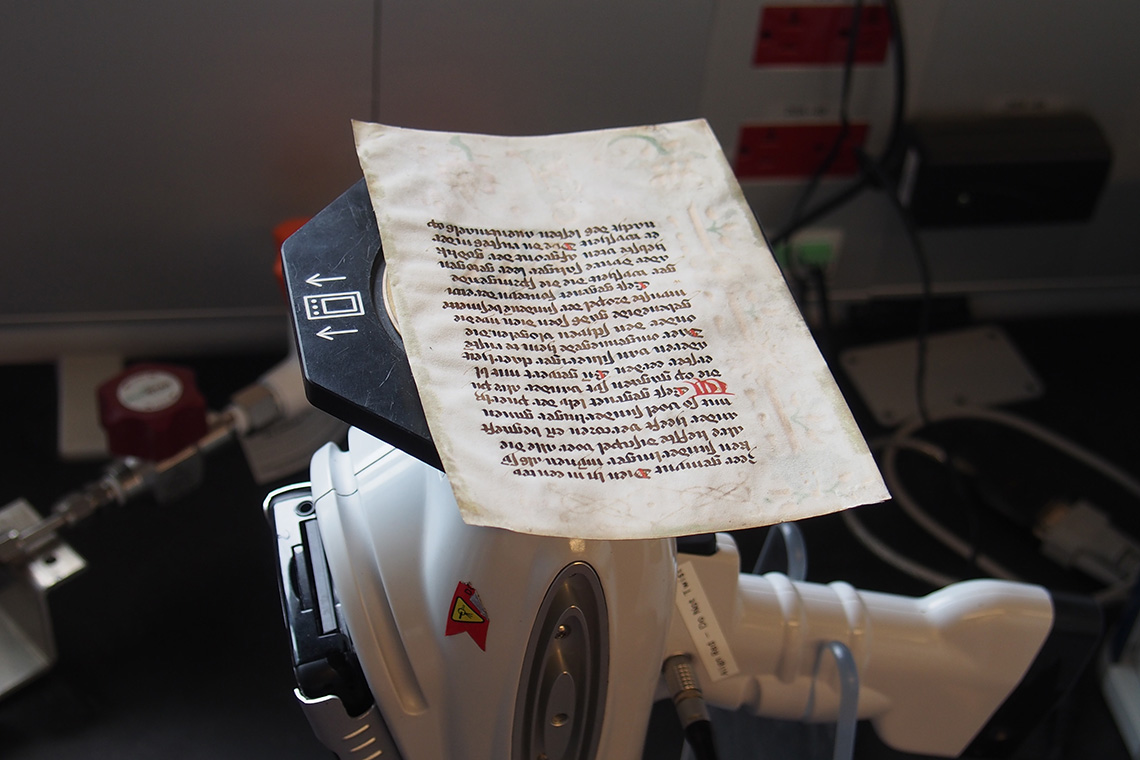

One of the technologies used was an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) hand-held spectrometer, which offers a safe and non-destructive look at the chemical elements of a sample, particularly metals in objects such as sculpture, jewelry and decorative pieces. Certain blending of materials are unique to specific time-periods, which helps to identify when and where they were made, and also allows for proper conservation of objects and their full description.

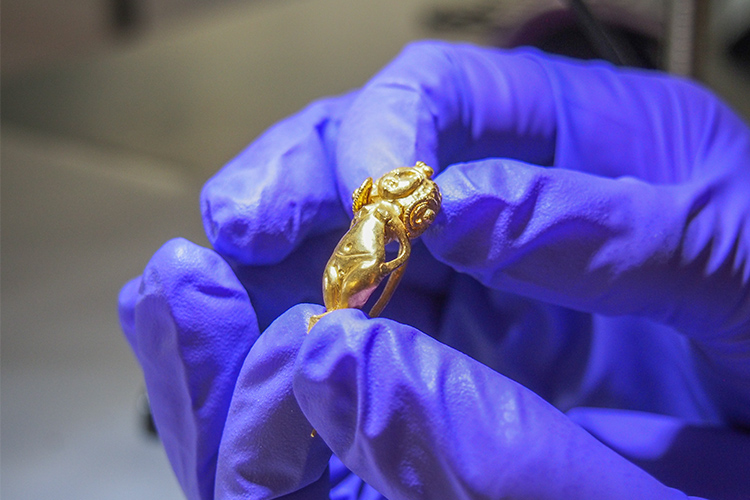

Rashana Youtzy studied Christian objects, including an oval-shaped pendant. The pendant, which has a raised image of the Virgin Mary holding a post-crucifixion Jesus on its surface, is carefully lined with leaves around its frame.

“Holding an object that is centuries-years-old amazes me,” says Youtzy, a fifth-year U of T Scarborough art history student. “I found it really enticing that I could contribute to the field and not only mark a check-point in my academic career, but also in the lives of the artworks.”

Working with Liam Bryant, a third-year art history specialist at University College, the group used XRF analysis and digital microscopy to accurately date the pendant down to the half-century, rather than a hundred-year gap, predicting that the two objects they studied were from the European Renaissance – and likely produced in Italy.

“Initially we had read that the pendant was created in the 17th century and made with white bronze, then on a different file it had silver written as the material,” Youtzy says. “Through our analysis we established the material as silver, and after studying silver-working processes alongside the stylistic analysis we could claim it was made in the 16th century.”

Le Anh Chau Tran, a third-year arts management student, studied features of a manuscript from a Dutch prayer book. While it was suspected they contained gold, no one had ever done a material analysis on them before. The group figured out that parts of the manuscript were made with real gold, meaning it was likely made for elite patrons.

“The intersection between the humanities and chemistry worlds has the potential to be a discipline in itself,” Chau Tran says.

Hadzovic says there’s potential for an interdisciplinary approach beyond the program itself.

“I’ve had chemistry students tell me, ‘I didn’t know I could work in an art museum,’ but you can,” Hadzovic says. “I want to constantly show students the possibilities they have in the field and the different challenges they may meet as they navigate the space of chemistry.”

Bryant hopes to become an art conservator in the future. Since it’s hard to find art conservation classes at the undergraduate level, he used the opportunity as a way to get experience in a related field.

“The Scholars-in-Residence program allowed me to really see what my future could look like in a sincerely palpable way,” Bryant says.

“I suggest applying. Depending on the project, you really have the opportunity to distill a very abstract idea of your future down to an academic reality.”

Hadzovic and Webster are offering a joint fourth-year research-based seminar this winter that has grown out of the SiR project. It will bring art history and chemistry students together for further study of Malcove objects.

This article was originally published by U of T News on December 10, 2019; reprinted with permission.