Visual art is the harmony to music’s melody, believes Samantha Chang.

To better understand and celebrate this connection, the professional flautist, conductor and PhD candidate with the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of Art History, is teaching a new fourth-year seminar, Music and Art in Early Modern Europe.

This seminar examines how music, architecture, sculpture and painting were intertwined across early modern Europe — the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries — with students exploring how the music-art relationship developed from that period to today.

“A musical element really adds value to the visual sense, it heightens the visual sense,” says Chang who calls herself an ‘art historian by day, classical musician by night.’ “There's a lot of overlap and this course really breaks that down.”

Chang loves the art-music connection, focusing her research on how painters of early modern Europe blended artistic and musical identities through the creation of self-portraits — often posing with instruments or sheet music.

“I describe it as the study of the selfie culture of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries and the question I try to answer is why the painters portrayed themselves as musicians,” she says.

For Music and Art in Early Modern Europe, Chang doesn’t just look at the lives of kings and queens She explores the lives of common Europeans and uncovers their relationship to music and art in their homes and day-to-day lives.

“That's the fun part,” says Chang. “We're looking at all classes but it's hard to find evidence of music-making in the home because unless somebody wrote a diary, it's hard to keep track of what was going on.”

But that’s the historical investigation she relishes, continually asking her students, “How can we study the everyday rather than the exceptional?

“I always tell all my students that I love being an art historian. I feel like Sherlock Holmes trying to piece together all the little clues and trying to formulate a view into the past — and students really connect with that.”

Students are also connecting with Chang’s ‘choose your own adventure’ course format.

“Students pick everything — the topics, the assignments, the due dates,” says Chang. “This is truly a course where I've catered to the learners. I'm just there as a facilitator and the students love that. They're very invested and engaged because it’s something they have chosen for themselves.”

“I love the approach Samantha is taking,” says Anna Nersisyan, a fourth-year art history student and a member of Woodsworth College.

“It is a lot less formal than what most U of T courses have been like in my experience. It gives us enough freedom to focus on what we enjoy doing, but also to think of something new that we haven't tried in the past.”

For example, Nersisyan’s favourite assignment so far involves her creating an audio guide for a fictional museum exhibit.

“This is definitely outside my comfort zone, but I’m excited about it for that reason,” says Nersisyan. “My plan is to compare and contrast the modern-day experience with music that we have now with what it would have been like in early modern Europe.”

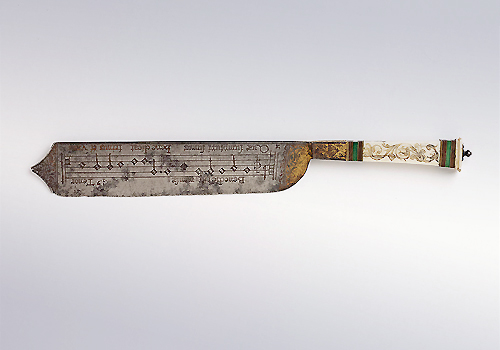

This knife dates from the first half of the 16th century and is probably Italian. Its blade is engraved with musical notes and blessings to be said before and after a meal. Knives with musical notes on the blades are known as notation knives. Image: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Jamie Harris, a fourth-year student, specializing in critical practices in visual studies at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, & Design, took this Arts & Science course because she plans to live in the United Kingdom and pursue a career in Europe’s art scene. She’s especially enjoying the ‘miniseries music supervision report.’

For this assignment, students choose the music that will accompany a fictional streaming TV series that highlights an important historical event. Instead of selecting music from the period, Harris is pairing mock episodes with contemporary music. In her final report, she has to outline the reasoning behind her selections.

“It's an exciting, contemporary way to understanding how music and art in early modern Europe has developed and influenced the field today,” says Harris. “I can analyze and compare the similarities and differences between various types of music scores, as well as the use of instruments and narrative structures.”

“As the instructor, I’m excited because I get to listen to music from the student's playlist while reading their report,” says Chang.

“We also talk about historical strategies of using musical arts, but we also talk about current strategies,” she adds.

One example is the recent United States presidential inauguration.

“How was music used in the inauguration?” she asks. “What did it mean to have Lady Gaga sing the national anthem? How does that compare to the political agendas of the 17th century? What did King Charles II do musically for his procession through London? There are a lot of parallels.”

At the end of this course, Chang hopes her students come away with a heightened awareness of the art-music connection and apply their historical knowledge when navigating careers or other artistic pursuits.

“It's getting them to think outside the box and apply history to almost any job because history dictates a lot of what is happening now.”

This article was originally published by A&S News on February 17, 2021; reprinted with permission.